TAMPA (Fla.) — Saturday is the most crucial day for baseball’s efforts to save its season. Major League Baseball intends to present a proposal it hopes will defibrillate negotiation on a new collective bargaining arrangement. If you want to feel the crackle of the bat or inhale the smells of a ballpark, MLB should make a big move. It could be the key to Opening Day.

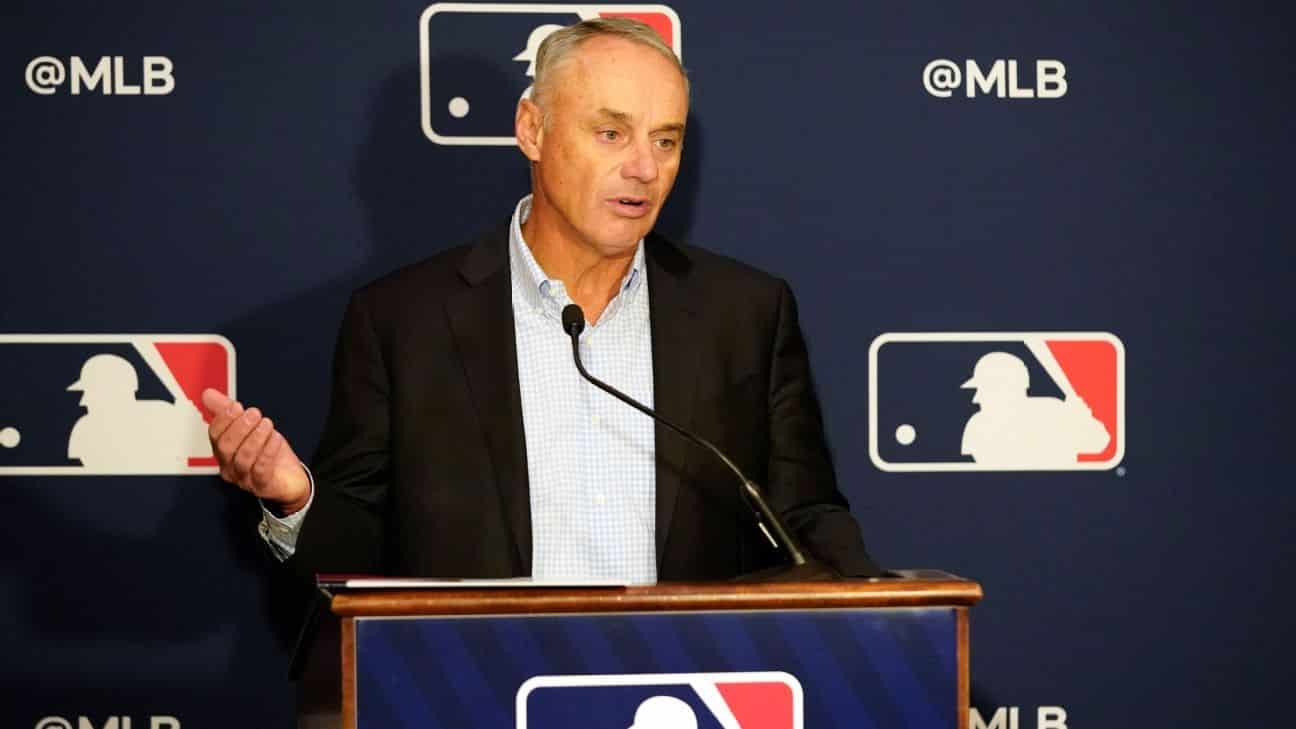

Rob Manfred (commissioner) is the person responsible for negotiations on behalf of the league. spoke ThursdayFor the first time since Dec. 2nd, he had locked out players. Seventy-eight days later, the MLB lockoutHe attempted to project optimism and assured that baseball would continue on a regular schedule. (Missing games, he stated, would be a “disastrous outcome for the sport).

Manfred was able to demonstrate why players feel so angry despite the lack of pacifism. He argued that investing in the stock market is more lucrative than owning a team of baseball players, and mangled facts about a crucial part of negotiations (through Manfred’s spokesperson, Manfred claimed he misspoke). He also stated that “I am the same person today” which does not speak well for someone leading a sport in 2022.

Let’s start by comparing Manfred to the era before dial-up Internet. It is important to understand the context. Manfred answered a question about public criticisms and said, “I don’t.” [pay] a lot of attention to social media, to be honest with you,” he said — Manfred cut off the next question to point to his résumé as a negotiator: “In the history of baseball, the only person who has made a labor agreement without a dispute, and I did four of ’em, was me. After four negotiations, players and union representatives were able to trust me enough that they made a deal. Today, I am the same person I was when I started that labor job in 1998.

Manfred, although inelegantly, stated that he has done previous deals and that any change in this process is less on his than the MLB Players Association, namely Bruce Meyer who is the players’ lead negotiator. This is the most charitable interpretation. Yet, even though baseball is at its current place, facing down the postponement spring training and possible loss of regular season games, Manfred is basically blaming the other party. In response to a previous question about why negotiations were so slow after Dec. 2, Manfred replied that “phones work both ways”. This doesn’t really reflect the friendly nature of a dealmaker.

Manfred’s words, taken literally, reveal a commissioner whose mindset is rooted in the previous century. That notion seems to be supported by MLB’s position regarding the value of its teams. Manfred was simply asked the simple question, “Would it be a good investment to own a baseball team?” Manfred answered the question as follows:

Manfred stated that they had hired an investment banker to examine the issue. “If you take a look at the purchase price for franchises and the cash put into them during their ownership, then the sale price, historically the return on these investments is lower than what you would get in the stock exchange. You take on a lot of risk.

It is important to remember that 30 men chose baseball teams over investing their money in the stock exchange. Focus on the facts and show that at least one team is worth the investment. Atlanta BravesThis is an excellent investment.

Liberty Media is the Braves’ owner. Their financials are made public in statements. The latest statement covers the third quarter 2021, which ran from July to September, just before the Braves won their World Series. Liberty reports that the team’s operating income (before amortization and depreciation) was $55million in that quarter. This is not a new phenomenon. The OIBDA of the team in 2018 was $88 Million, while it was $49 Million in 2019. They also lost $53M during the COVID-shortened 2020 Season. That’s not including the tax benefits organizations get through amortization or depreciation.

In 1998, billionaires were not as prominently seen in the United States as they are today. This rhetoric, that baseball teams weren’t profit centers, was a common feature of the league’s bargaining position. Owners have long maintained that their finances were a black box and received little criticism from outside media. In an interviewSt. Louis’ Bill DeWitt, who was the editor of 590 The Fan during the summer 2020, stated that “The industry isn’t very profitable, be quite honest and I think [players]That is understandable. They think the owners are hiding profit, which is why they don’t understand.

These days are gone. DeWitt ought to have realized by now that such distrust stems, perhaps, from owners of baseball clubs calling their industry not very lucrative. Manfred is well aware that there will be backlash if he attempts to cover his 30 bosses by downplaying the wealth in the sport during a labor negotiations that is, at its core, about money. Yet, the league’s thinking continues to be this: it’s easier to argue that players get enough money if owners don’t make any bank.

Yet, at least some people still believe in the league’s point of view. A December YouGov poll found that 53% of respondents believed MLB players were being paid too much. The poll also asked respondents who they believe is right in relation to the labor dispute: players or owners. Sixty-seven per cent said they were not sure. 23% were for the players, and 11% for the owners.

This is a significant change from the previous labor stoppage when CBS/New York Times polls showed that 40% of respondents thought owners were more right-leaning and 19.9% supported the players. As much as owners would like it to be, such a paradigm shift in the negotiations should not be ignored. While public perception doesn’t create deals, it does help to shape them.

Manfred was the leader of the negotiations and MLB turned the power dynamic in favor players’ favor over the past two decades. The league’s strategy was successful and has been reflected in the five-year basic agreement, which expired in December. Industry revenue grew. Salaries decreased. This simple fact is what underpins radicalization among players who see Manfred the avatar of the ownership class he represents.

The treacherous minefield that the commissioner must navigate is daunting. The players demand more. Owners aren’t willing to spend more. His legacy is at stake. Is he really a consummate dealmaker, or is he just trying to be one in public.

Saturday’s gathering will mark the fifth core-economics meeting for both sides since the lockout began. Since then, the union has not changed much from its previous positions. The union renounced its earlier request for free agency for players and dropped its request for a revenue sharing reduction of $100 million to $30million — subjects the league claimed were non-starters. The league’s position on minimum salaries, arbitration eligibility for players who have served two years or more, and service-time manipulation has remained unchanged. Angered by MLB’s latest proposal, the union responded with a reduction in its pre-arbitration pool of $100 million to $100 millions.

The league has also remained largely unchanged. It increased its minimum salary proposal from $600,000.00 to $615,000. It accepted the bonus pool idea and offered $10million, which is less than one tenth of the amount the union requested. MLB is still awaiting changes to revenue sharing or arbitration. Its draft lottery, which was offered before the lockout saw very few revisions. The biggest move by the union was offering draft picks for teams that have a high-achieving player to play for a full year. The union is seeking the plan to add to its proposal that players can earn a full-year of service through performance.

The competitive-balance tax has not been mentioned by either side since the lockout began. It made an odd appearance on Thursday. Manfred answered a question Thursday about the competitive-balance tax, saying that the league had presented rates of taxation that were “statusquo.” This was incorrect. Recent years have seen a 20% tax rate for teams above the $210million threshold, 30% at $230million and 50% at $255 million. MLB proposes a 50% rate for teams above $214 million, 75% for $234 million, and 100% for $254 million. A third-round draft pick would be lost by teams at the first threshold.

CBT was already a thorny subject for players. Revenue grew in recent years, but the top rates remained stagnant. Manfred’s incorrect description of it may have been an innocent error, but it nevertheless highlighted the huge gap between the parties and the fragility of these negotiations.

Manfred’s optimistic outlook requires action. He didn’t want to delay the opening for spring training. Everyone in the sport knew that players would not be attending camps next week. It will probably happen after Saturday’s league offer — Manfred called it a “good suggestion.”

Good is relative. Good is sufficient to get the negotiation going in order for both sides to reach a settlement. Good is no longer incremental. Not with February ending three weeks away and Manfred declaring he wants four more weeks of springtraining before the season starts. Good recognizes that things have changed in society as well as in the union and that MLB can, and will, change with them.

If Saturday brings less, players will continue to work harder and regular-season games could be at risk. Owners assume that the union is waiting until a deadline like the soft one at either the end of February, or the beginning March to move things along. Manfred stated Thursday that all it takes to move negotiations from a standstill into something more productive is one moment. The league has that opportunity.

It’s clear what comes next, otherwise. Manfred stated it himself. It’s the worst outcome anyone can wish for.